This is an article first published by me in in HACKNEY HISTORY.

I acknowledge the help given by Hackney Archives and by the Friends of the Archives.

A Nose for Sawdust

Sheffield born Henry Tyzack, the sawmaker, was thirty years old in 1839. He was at that age when the ambition of youth blends with the confidence of maturity. At thirty, unable to resist the lure of a good market for saws, he moved his family to Shoreditch. They settled in Curtain Road.

Curtain Road, in the 1840s', was the home of the furniture industry. Furniture uses wood and wood cutting demands saws. Henry had a nose for sawdust. Until the mid-nineteenth century the quality firms of the West End and City produced most of the furniture made in London. From about 1840 there arose a demand for lower priced furniture. The East End trade developed to meet the need. It started mainly with chairs but soon grew to cover most articles. The mainstays of the East End trade were the small workshops where long hours produced cheap furniture. Most furniture workshops, even those of the West End, were accessible to a lively saw merchant from Curtain Road.

The Napoleonic wars caused a dock building boom. It attracted thousands of labourers and their families to the East End. The area developed an industrial character but overcrowding from the City brought a threat of disease. By the year 1799 a large vinegar works, built on the north-east corner of the City Road and Old Street, added to the malodour of the area. Housing conditions rapidly worsened in the 1830s'. Smoke from the brick yards cast a pall. There were many timber yards but the largest was the City Sawmills in the New North Road. Cabinet makers, chair makers, carpenters and houses used as furniture making shops operated all over the locality. Chair work was broken into stages with a single item passing through several workers. Each would perform a few operations. Workers often worked with their families in the one or two rooms of their home. They crowded into the courts and alleys of the area. South of the parish was the centre for the furniture trade but impoverished poor in increasing numbers were packed into thousands of identical dwellings. They were victims of the population explosion. In 1821 Shoreditch had 53,000 inhabitants. By 1841 there were 83,000 and this number reached its peak in 1861 at 129,000. In 1839 the second Commons Select Committee on Metropolitan Improvements published ideas to stop the growth of filthy and unhealthy slums, including Shoreditch . Maps with the report showed demolition and new roads just south of Old Street but high costs prevented the scheme going ahead.

Henry's move corresponded with the opening of the Sheffield to Rotherham Railway line and the line from Masbrough to London. Masbrough is within a mile of Rotherham's centre. Before the Masbrough station had opened in 1840, the only way to London was by coach. Journey time from the Tontine Inn was little short of twenty-six hours. The Tontine Inn was about a mile north of the present site of Sheffield Railway Station. It was built roughly where Exchange Street is now. Thirteen coaches a day left the Inn. It had the hectic scene of bustle of any transport terminus. With Sheffield's growing links with the outside world of commerce, came an increase in traffic. The inn's courtyard rang to the clip of hooves, the rattle of wheels on the cobbles and the commands of the ostlers .

From Sheffield to Shoreditch

Then one day in May 1840 all fell quiet. From that day the North Midland Railway pulled into Wicker station Sheffield and made the journey to London possible in about nine and a half hours . Henry moved to Shoreditch around the time of the first trains.We don't know whether Henry went to Shoreditch to sell saws made by his relatives in Sheffield, or whether he was striking out on his own. A saw did not need much for its manufacture, just a fly-press, a vice for setting and sharpening and a small furnace. But Henry's younger brother Joseph had just started up a business at 160 Fitzwilliam Street Sheffield, and his father Samuel was also a sawmaker.

Figure 1

Trade mark used by brother Joseph after he had won a large contract from the IOM Steam Packetboat Company.

Perhaps the move may have been to act as London merchant for these or for the saw business of Henry's uncle, Thomas Tyzack. He also had uncle William who set up his Sheffield tool business as early as 1812. Much Sheffield output was exported. In spite of that, most of the exporting during the eighteenth century was done through London merchants . It is likely that Henry came to London originally, as the marketing arm of the family businesses.

Henry Tyzack and his wife Sarah Story had seven children. We know the time of their move because daughter Louisa was born in Ecclesall in 1838. Her sister Elizabeth Harriett, was born in London in 1841. After Elizabeth, all of Sarah's children were London born.

Figure 2

Map showing the location of Henry's premises.

Henry's first shop, No. 53, was located just east of Tabernacle Square and just before the exit of Crown Street but on the opposite side. Behind the premises were the alleyways of Bath Place. Just behind where the shops alongside No. 53, were later built, a natural spring had been used, from the seventeenth century, to cure rheumatic pain. The baths there were large, twenty feet by thirty feet . Henry's shop was just three hundred yards from the large notorious vinegar factory built by 1799, on the corner of Old Street and City Road. On the opposite corner was the City of London Lying-in Hospital, St. Luke's, a purely charitable institution. Sarah produced three of her children in its beds, Elizabeth, Maria and Frederick. Matron Mary Widgen reported the births. She must have been a stickler for promptitude. Henry and Sarah had not even decided on a name for poor Maria when her birth was reported. Just Female Tyzack, it says in the index.

Although Henry went to Shoreditch in 1839 his address there does not show until 1846, in the birth certificate of son Ebenezer. Then, by 1848, nine years after he came to Shoreditch, he took the shop at No. 53 Old Street. His neighbours were as shown below.

| 47 | Thomas Mundy | Butcher |

| 48 | William Morgan | P. Surgeon |

| 49 | Thomas Robson | Fixture Dealer |

| 49 | Henry Chas. Simpson | Hairdresser |

| 50 | Frederick Cordaroy | Hatmaker |

| 51 | Samuel Andrew William | Hairdresser |

| 53 | Henry Tyzack | Saw and Toolmaker |

| 61 | Jas. Peak | Fixture Dealer |

| 62 | Owen Owen | Turkey & Whetstone Mnftr |

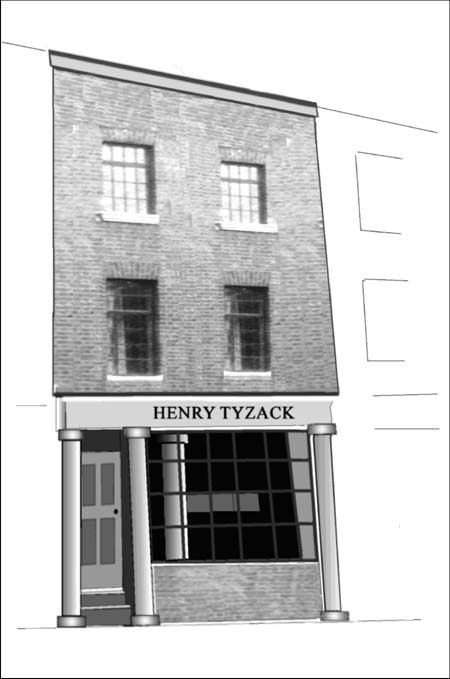

Figure 3

Drawing of what No. 53 probably looked like based on surviving shops around.

There were some others between Nos. 62 and 68 and then came the Tabernacle. Henry took over the shop from John Taylor a whitesmith. Today we would call John Taylor a tinsmith, a worker in tinned or white iron.

This was a good centre for the furniture trade. There were many small businesses ranged around, down to home workers making one component. There are still some, even today. Furniture ruled. Take Hoxton Market, just off Boot Street, where later we find Henry, of seven listed addresses, apart from the George & Dragon, the remainder were furniture makers.

| J. | Goddard | french polisher |

| A. | Keer | cabinet manufacturer |

| J. | Burgess | easy chair and couch manufacturer |

| W. | Wilkins | cabinet manufacturer |

| T. | Crawley | chairmaker |

| C. | Hughes | cabinet manufacturer |

Close by in Curtain Road, there were two timber yards. Another large one lay behind what was later to become the site of son Samuel's shop at No. 8 Old Street.

Sarah died on 18th April 1848, at No. 53 Old Street. The family lived over the shop. She was only thirty-nine and died of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Clearly the living conditions of the area did not help Sarah at all.

Figure 4

Knifeboard bus of the type operating in Old Street circa 1850

Henry was a fast worker, just eighty-five days later, on 13th July 1848 he felt he'd left enough time for appearances and married his second wife, Louisa Wheeler. Then he again recorded his trade as a sawmaker.

Henry's 1851 census return shows he was employing one man.

In 1855 Henry and family left the house to which he had grown accustomed. He had first occupied No. 53 in 1848. His wife Sarah had died there and several of his Shoreditch children, including Louisa's, were born there. Now suddenly he abandoned No. 53. He went across the road and took up residence in No. 36 Old Street. His business went too. Why is not clear.

The previous occupant of No. 36 had been another Henry, Henry Wilson. Wilson was a leather seller, another supplier to the furniture trade. Next door was Jacob West at No. 37. Jacob was an ironmonger. That was more in keeping with Henry's trade. On the other side, James Sheath had his gutta percha factory. Modern plastics have almost washed out the memory of gutta percha. It was probably used then in upholstery. Later it found a use in golf balls and then in submarine cables. Today it still finds favour with dentists in filling root canals.

From Builder to Bankrupt

On the 31st March 1856, Thomas George Corbett of Elsham near Brigg Lincolnshire made a contract with a builder, Arthur Wilson. In view of the expenses borne by Wilson, Corbett would grant him the lease of a piece of land in Tower Street Hackney. During the building Corbett arranged that Henry Tyzack should build an additional house on the London Lane front of the site.Figure 5

Henry Tyzack signed the documents himself. This document was the first evidence that Henry could write. The Sheffield schooling system was very hit and miss. His was not a flowing hand. There are at least two hesitations in the signature. One can imagine a tongue firmly held in cheek while the procedure was in process. Henry signed this part of the deal but with his poor literacy may not have fully understood all the risks. Corbett, his adversary, was an educated man, with a master's degree from Oxford . Should Henry fail to make due payments, Corbett could terminate by applying for a declaration of Henry's bankruptcy !

Part way through the construction, with building materials all round, Henry stopped making further payments and did not proceed with the planned work.

Corbett gave notice to end the building agreement and Henry was duly declared bankrupt .

At that date Henry was running his business of tool manufacturing at No. 36 Old Street and at No. 11 Boot Street. At the time of the settlement there was a large stock in trade and other articles and materials in and about these houses and buildings.

To avoid further strife and litigation Corbett's solicitors, Bartle John Laurie Frere of Lincoln's Inn, made a proposal. They suggested that the creditors' assignees, Robert Marsden, a toolmaker of Sheffield, and James Miles, a lead and glass merchant of Shoreditch, should buy the rights and interests of all building, and other materials about the premises. Marsden and Miles should also buy all stock in trade and goodwill articles of Henry Tyzack. Marsden and Miles offered six hundred pounds. Robert Marsden and James Miles gave their opinion that it would be to the benefit of the creditors to accept the offer!

Of the six hundred pounds, five hundred was considered payment for the stock etc. The balance of one hundred pounds was the money for the rights under the said building agreements. This valuation gives some idea of Henry's scale of operations at this time, (1858). A bradawl at the time cost about two and one half old pence, a jack plane say five shillings. Therefore, this amount represented maybe about four thousand pieces.

With the bankruptcy order in his pocket, Corbett arranged to sell all Henry's chattels and used five hundred pounds to pay for the seized goods. With the remaining one hundred pounds, he bought out Henry's rights under the Corbett agreement. Henry thus finished one hundred pounds worse off, plus all the disruption of his business and with the loss of any interest under the building agreement. How much he had left, if any, after clearing his other creditors is not clear.

Marsden and Miles were given the right to enter the premises of No. 36 Old Street and No. 11 Boot Street. There they could take possession of the stock etc. and all the books of business relating to it. That bit must have caused some irritation ! Just imagine a competitor toolmaker with the right to take your list of customers' names and addresses.

Henry's tough break, perhaps from lack of reading skill, did not deter him. He seemed to push on with his business, because work at No. 36 Old Street continued until 1861, when Henry was fifty-three years old. He appeared there in the 1861 census when he was employing two men. Nineteen years old Elizabeth, his daughter, was also a sawmaker there. Soon after all this the business was transferred to his son.

From Father to Sons

Henry had been a man of adventure. Samuel, the eldest son, did not seek his fortune elsewhere, like his roving father. He simply settled for a smoky old shop next to the railway station.Figure 6

About 1920. Just before the shop was pulled down and rebuilt, grandly.

In 1860, Samuel acquired the lease of No. 8 Old Street, probably with dad's help. No. 8 was the plot right up against the North London Railway line, next to what became Shoreditch Station. No. 8 did not appear as an address in 1853, only No. 9. By the end of 1850 the railway had linked Camden town with the Docks. The North London Railway line from Kingsland to Broad Street Station was built and opened in the year 1865. Broad Street Station was opened in 1866. An act dated 26th August 1846, 9 & 10 Vic. c. cccxcvi, enabled the North London Railway. There must have been great railway building works alongside No. 8, (later No. 345). It was right next to the bridge, which is still there, an ugly iron box. In the 1871 census, Samuel reported five employees, at No 345. That year he signed a twenty-one year lease for 50 pounds per year for the shop. However, on the 6th January 1871 there was a renumbering ordinance. Thus, in place of No. 8, we find Samuel now in possession of No. 345.

In 1877 the North London Railway, which was the freeholder, put the lot up for sale. Altogether it totalled fifty feet by thirty-two feet, a mere sixteen hundred square feet. Samuel must have taken the opportunity to buy it because when he died on 3 August 1903 Samuel bequeathed the freehold of Nos. 343 and 345 Old Street to his wife Emily, his son Horace Tyzack and son-in-law Henry Dunkley Carter.

He left all his business interest, goodwill and use of the freehold in the property to his son Edgar Tyzack, 1877-1959. Edgar's business was also charged to pay £1,000 between his brothers and sister, Horace, Arthur, Emily and Oscar. Edgar found this an enormous burden for the run down state of the business after Samuel's long illness. He challenged the bequest in court but lost. Edgar eventually prospered and rebuilt the business. A catalogue, printed on credit for Edgar, about 1910 lists over 3,000 different tools, mostly imported. By now there was another shop. As well as the one at Nos. 343 & 345 Old Street, there was one at No. 153 Shoreditch High Street.

Henry and his second wife Louisa had a daughter and a son.

Walter Henry, the son, was born in the last quarter of 1853, in Shoreditch. In 1869, when he reached sixteen, his father Henry, aged sixty, sniffed sawdust again. This time Henry took his son, Walter Henry, and his wife Louisa to High Wycombe, in Buckinghamshire. That was in 1869 when Henry realised that the furniture trade was no longer confined to London and the area around Curtain Road. We find all three of them at No. 29 Oxford Street on the night of the 1871 census. As usual dad was head of the household and a sawmaker but Walter Henry also was already called a sawmaker. A most sizeable furniture industry had become established around High Wycombe, in Bucks. A trade directory published a few years later, "The Directory of High Wycombe 1875", records a daily output of four thousand seven hundred chairs.

Walter Henry served there in the shop at No. 29 Oxford Street High Wycombe when he was sixteen. Over the shop it said, "Henry Tyzack Saws". Again Henry's nose for the furniture market had found another centre of the furniture industry irresistible. Walter Henry remained at High Wycombe although Henry, his father, returned to live in Hoxton by 1875.

Walter Henry had two sons. One became mayor of High Wycombe in 1931. The other became the proprietor of a furniture factory in Slater Street in 1907. There is a Tyzack Road in the town named after the Mayor of High Wycombe, 1931-2 .

Return to Shoreditch

High Wycombe was too dull for Henry. His son, now set up there in business, could be trusted to look after that shop. Shoreditch with son Samuel's shops and the business of the other sons had more action. Whatever the main reason, by 1875, Henry, probably partially retired, was back living at No 7, Somerset Place, Hoxton. Henry died in 1876 and his second wife Louisa outlived him by twenty years.Shoreditch, covered just one square mile. It had grown faster than any other London parish in the first half of the century. Demolition made in the 1860s', for the building of the rail link between Dalston and Broad Street, moved many local people. It came within a few feet of ousting Samuel at No. 8. Sanitary conditions began to improve after the passing of the Metropolis Management Act of 1855. A turning point had come in 1864 when the sewer system for the Metropolis was completed. The Times of 18th August 1873 said, "London has been transformed in a comparatively brief period if not into a clean, at least into a healthy city. .... The Board of Works has done itself credit." The locality had many almshouses, public houses and theatres galore.

After the eldest son Samuel died in 1903, the Tyzack shop by the station remained in the name of Samuel until 1905. From 1905 the directory records that Edgar renamed the shops, by then Nos. 343 to 345, as the premises of "Samuel Tyzack and Sons". Edgar had no sons, which was probably the reason he tried, unsuccessfully, to adopt my father. Late in his life Edgar had a daughter Margaret, and the shop by the station continued to trade under the family name until about 1987. The site was then sold and the business moved a few doors away to No. 329 Old Street. This had been part of Parry's tool-business until Parry died, when it had been offered to and taken over by Edgar Tyzack. Now a smart green sign says Parry Tyzack. Alas there is no one with the family name there any longer.

Today a large redbrick building exists on the site of the shop at No. 345. It no longer carries the name Tyzack.